Selfcare: medical devices and food supplements – a win-win combination

Selfcare, also called self-medication, has transformed healthcare habits: the patient-consumers now seek information, compare products and make choices. In pharmacies, medical devices and food supplements are displayed side by side, sometimes for common indications (sore throat, digestion, skin, weight management), yet they aren’t based on the same mechanisms of action or the same intended purpose. However, this product combination can become a winning strategy: complementary responses for consumers, and an effective high-performing product range for selfcare brands.

Since the COVID pandemic in 2019, taking care of one’s health and well-being proactively (and preventively) has become an integral part of everyday life, a form of responsible self-medication now firmly embedded in health behaviour.

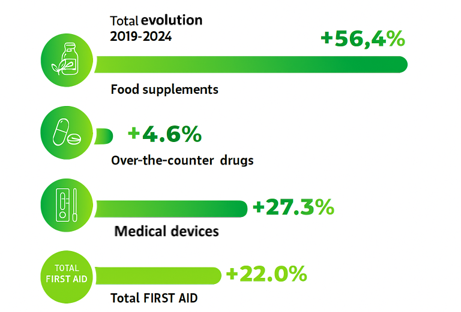

The success of the selfcare market in a few figures

According to NèreS (formerly AFIPA), the selfcare market includes first-line products, that is, non-prescription medicines, food supplements, and medical devices available in pharmacies. Between 2019 and 2024, the sector recorded overall growth of +22%, driven by an increase in the number of visits to the pharmacy (in France): 340 million in 2024, compared with 297 million in 2020.1 The COVID-19 pandemic acted as a catalyst, leading many French people to turn to their pharmacist as their primary healthcare provider for supervised self-medication.

More specifically, food supplements recorded the most significant growth +56.4%, followed by consumer medical devices, up +27.3%, while non-prescription medicines posted more moderate growth of +4.6%.

Evolution of first-line health products between 2019 and 2024

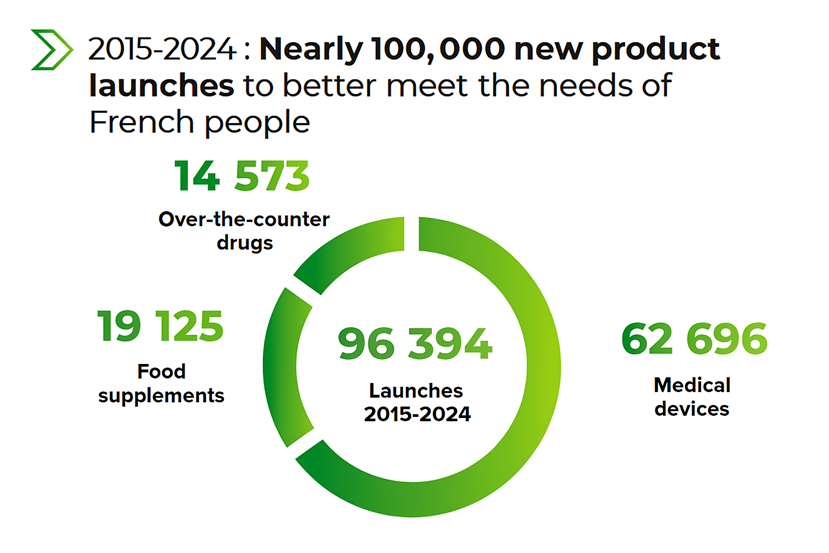

It should be noted that medical devices now represent the majority of launches over the past five years, confirming the dynamism of this product segment within the selfcare product range offering.

New first-line product launches between 2015 and 2024

The main health concerns are focused on sleep and stress (+8.7%), vitality (+4.9%) and the digestive system (+4.5%), needs that reflect everyday priorities.1

Food supplements and medical devices: two regulatory frameworks, a complementary role in selfcare

These leading categories in selfcare are nonetheless competitors in different disciplines, subject to distinct rules and regulations.

Under European law, a food supplement is a foodstuff presented in doses that has a nutritional or physiological effect and is intended to supplement a normal diet.2 Its claims are strictly regulated: it may make nutritional or health claims, such as “contributes to…”, but may not make medical claims such as preventing or treating a disease.3

In France, its first marketing authorisation is obtained through a teledeclaration procedure (Compl’Alim), with no systematic third-party assessment prior to marketing. The manufacturer remains fully responsible for compliance.4

A medical device, on the other hand, belongs to the field of health products. It is intended formedical purposes, such as preventing, diagnosing, treating or alleviating a disease or injury, but its principal mode of action is not pharmacological: it is mechanical or physical (forming a protective film, lubricating, adsorbing, creating an anti-reflux barrier, etc.).5 Its claims are medical claims and must be fully consistent with the intended use. In terms of evidence, the rule is clear: a clinical evaluation is required, proportionate to the device’s risk category (see box below).6 7

Marketing is achieved by obtaining CE marking, following a conformity assessment by a Notified Body (for the majority of medical devices, except most Class I devices, where self-certification is sufficient). This marking, which is valid throughout Europe, is a guarantee of the product’s safety and clinical performance, allowing the use of medical claims strictly related to the intended purpose.

These regulatory frameworks position the two categories differently but in a way which is complementary: medical devices provide enhanced clinical reassurance and claims more directly focused on symptom relief, while the food supplements are focused on physiology and prevention.

This complementarity is also reflected in the possibility of grouping medical devices and food supplements under a single umbrella brand, offering consumers a common reference point, provided that the claims and presentations are clearly distinguished to avoid any regulatory confusion or misleading communication.

Scientific reassurance and proven efficacy: the strengths of medical devices

In the world of over-the-counter health products, consumers are primarily driven by the effectiveness promised by the brand and express a clear need for guidance when making their choices. According to Synadiet, 81% of consumers state that the product’s claims are their first selection criterion.8 A European-wide survey conducted by Ipsos 2022 even reveals that 81% of Europeans consider it essential to receive a recommendation from a trusted source — doctor, pharmacist, family, friends or even the internet — and that nearly half of non-consumers would consider purchasing a product if it were recommended by a healthcare professional.9

In this context, the transparency of claims and the reassurance they provide play a decisive role.

Example with Humer Pharyngite, a medical device marketed by the Urgo Group10: the product’s clinical support is highlighted by strong claims such as reducing pain and inflammation. There is also a clear desire to offer a solution combining the scientific robustness of a medical device with naturalness: “A formula that draws its strength from the synergy between science and nature.”

A medical device can make genuine medical claims, supported by a clinical data required when they are marketed. This scientific and regulatory validation reassures consumers who are increasingly seeking proof of efficacy and safety.

Prevention and traditional use in selfcare: the benefits of food supplements

Food supplements, on the other hand, meet strong expectations in terms of prevention and staying in good health: seasonal immunity, digestive comfort, stress management, or skin beauty, among other things. Their value lies in the diversity of ingredients they offer: vitamins, minerals, fatty acids, but also plants whose traditional use benefits from long-standing experience. Whereas the medical device acts directly on symptoms, food supplements generally act at an earlier stage, helping to limit the onset of disorders. They can fulfil its primary function of creating an environment conducive to long-term well-being, but also take over afterwards, facilitating recovery following a symptomatic episode.

Supplements and devices: useful differences and strong synergies supporting selfcare

The example of GaviDigest perfectly illustrates the specific positioning of medical devices within the digestion sector. Developed by Reckitt Benckiser, this selfcare product designed to combat flatulence and bloating claims rapid efficacy within two hours, based on TransiProtect® technology.11 This technology forms a protective layer on the intestinal walls, providing a mechanical action that soothes, strengthens and restores to limit the recurrence of symptoms. The formula, composed of tamarind seeds and pea proteins, is supported by clinical validation.

Based on the same indication, the 5-Day Reset food supplement from the digital brand Dijo makes claims such as “helps reduce bloating”.12 Its claimed efficacy is based not on a mechanical action, but on the use of ingredients traditionally recognised for promoting good intestinal transit, notably caraway and fennel, combined with carbo activated charcoal.

In the weight management sector, a medical device based on adsorbent fibres targets the reduction of lipid and carbohydrate intake through a physical effect, while a food supplement addresses nutritional and metabolic balance. An example can be seen with the two complementary solutions by Pomeol13: the Acti Ball® Fat Binder (a medical device composed of plant fibres) and the Super Metabolism food supplement (containing vitamins B2 and B6, dandelion, and chromium).

Same indication, different promises, complementary benefits.

Let’s build together the selfcare range that will make a difference

In a booming selfcare market, the success of a brand depends on the consistency and relevance of its product range strategy. Food supplements and medical devices are not in opposition: they complement one another and each in their own way, offer solutions in line with consumer expectations.

The key challenge lies in defining the most relevant combination according to the product range’s target and positioning. It is precisely in this strategic reflection that BOTANIBRANDS intervenes, bringing its dual expertise in food supplements and medical devices.

We support brands at every stage to:

- Define the optimal product range strategy based on market positioning and target expectations.

- Provide medical devices for in-licensing, turnkey solutions for rapid market access.

- Conduct technical and regulatory due diligence of medical devices to secure their integration into a brand portfolio and their market release.

Would you like to transform your ideas into high-performing selfcare solutions?

| Focus on oral medical device classes (EU) General principle: classification (I to III) depends on the level of risk. The higher the risk, the greater the clinical and regulatory requirements prior to CE marking. Class I: low risk, such as non-invasive devices with local mechanical action. Examples: dental accessories (mouthguards, protectors), classic dressings. Class IIa: moderate potential risk, such as invasive devices for temporary (<60 min) or short-term use (<30 days). Examples: film-forming throat sprays or lozenges for irritated throats, oral gels for mouth ulcers or dryness, cough syrups, or intestinal wall protective films (e.g. GaviDigest) intended for the treatment of intestinal disorders. Class IIb: significant potential risk, such as invasive devices for long-term use (>30 days) or those that locally interact with the digestive function. Examples: fat- or fibre-binding devices for the treatment of obesity, preparations containing kaolin or diosmectite for the treatment of diarrhoea. Class III: high risk, such as implantable devices or long-term invasive devices depending on the part of the body concerned (heart, central nervous system, etc.), or those with a biological effect and devices incorporating a substance similar to a medicinal product — rarer, as they are often reclassified as medicines. These are subject to the strictest controls. Examples: cardiac implants, antibiotic-loaded bone cements, or intrauterine devices (IUDs) containing medicinal substances such as copper or silver. |

Sources :

- Baromètre NèreS 2024, Les pharmacies au cœur des évolutions de la santé de proximité.

- Directive 2002/46/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 10 June 2002 on the approximation of the laws of the Member States relating to food supplements

- Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 December 2006 on nutrition and health claims made on foods

- TeleIcare : déclaration en ligne de mise sur le marché d’un complément alimentaire https://entreprendre.service-public.fr/vosdroits/R44574

- Regulation (EU) 2017/745 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 April 2017 on medical devices, amending Directive 2001/83/EC, Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 and Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 and repealing Council Directives 90/385/EEC and 93/42/EEC (Text with EEA relevance. )

- MDR – Article 61 – Clinical evaluation

- MDR – Article 7 – Claims

- Baromètre 2024 de la consommation des compléments alimentaires en France, Toluna, Harris et Synadiet

- Consumer survey on food supplement in Europe – 2022 Ipsos

- https://humer-lagamme.fr/solutions/traitement-et-soin/gorge/humer-pharyngite/

- https://www.gavidigest.fr/nos-produits/flatulences-ballonnements/

- https://www.dijo.fr/products/5-day-reset

- https://pomeol.fr